Features on Asian Art, Culture, History & Travel

Archives

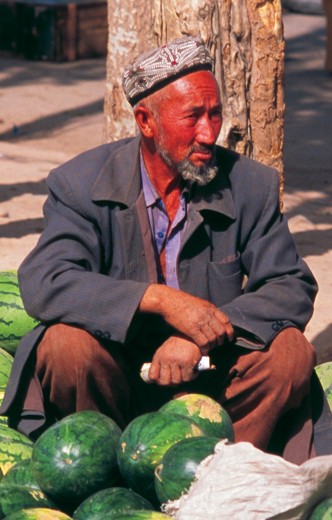

Archives > CHINA > Xinjiang

Xinjiang

Separatism In Xinjiang

SEE RELATED IMAGES @ PICTURES FROM HISTORY

Partly because of the successful information programme run by the Tibetan government in exile in Dharamsala, and partly because of the ham-fisted way the Chinese authorities continue to persecute Tibetans at home (the current campaign against pictures of the Dalai Lama being a good example) the world at large is well aware both of Beijing's presence in Tibet, and of the Tibetan people's continuing hostility to Chinese rule.

Less well known is the situation in China's other great Central Asian territory, the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, a predominantly Muslim province one-and-a-half times the size of Tibet, large parts of which have more in common with Afghanistan and the newly independent states of former Soviet Central Asia than with China proper. For decades Beijing has kept this remote region – home to the Lop Nor atomic weapons centre and a vital source of crude oil – out of the limelight. Occasional reports of resistance to Chinese rule by sections of the indigenous population filter out, but generally speaking Beijing keeps the lid screwed tightly shut.

It was exceptional, then, for details to emerge last week of a separatist incident which recently took place. According to the Xinjiang Daily, a group of nine armed men, identified only as "Muslims and splittists", were members of a "dare-to-die" squad which clashed with police near the town of Kucha, on the northern rim of the Tarim Basin. All nine, including the group leader – identified only as Abula Tuohuti – were killed. Xinjiang officials, clearly troubled by the incident, warned of a surge in "subversive bombings and separatist activities", and accused the rebels of trying to stir up a holy war. In a separate incident, a Muslim man was sentenced to three years in prison by a court in Urumchi, the provincial capital, for distributing "separatist literature".

Only last month Chinese Foreign Minister Qian Qichen announced that China and its Central Asian neighbours – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan – had agreed to join forces with Russia to combat the spread of Muslim fundamentalism in the region. This begs several questions. Just who are these "splittists"? Who, if anyone, provides external support for their cause? Do they pose a serious threat to the Chinese authorities? And, finally, is "Muslim fundamentalism" really a factor?

Beijing likes to assert that Xinjiang – like Tibet and the South China Sea – has been "an integral part of the motherland from time immemorial". This, at the very least, is an over-simplification. Han involvement in the area dates back two thousand years to the Western Han Dynasty, but Chinese control remained tenuous and sporadic until the mid-18th century. During this period the easternmost part of the region became increasingly Sinicised – but from around 1200 AD the independent oasis towns of the west, strung round the Tarim Basin like beads on a necklace, became a firm part of the Muslim World.

China's conquest of the Tarim Basin dates from 1755, when troops of the Ch'ing Emperor Ch'ien Lung advanced into the region. Within three years they had captured Kashgar, the Uighur capital, but were unable to consolidate their hold on a permanent basis. Over the next century the region was racked by four major and numerous minor anti-Ch'ing risings, ensuring that Chinese power never spread far beyond the main towns. This period of unrest culminated in the great revolt of 1867, when a warlord called Yaqub Beg expelled the Chinese and, proclaiming his fealty to the Turkish Sultan in Istanbul, proclaimed himself Khan.

It took the Ch'ing fully a decade to suppress the Uighurs and recapture Kashgar. Seven years later, in 1884, the Tarim Basin was joined with Zungharia and Ili to become, for the first time, a province of China. The Ch'ing authorities named it Xinjiang, or "New Territory" – a designation never appreciated by the indigenous population, who still prefer to call their country Dogu Turkistan, or "Eastern Turkistan".

When the Ch'ing Empire fell apart in 1911, the people of Xinjiang again rebelled against Chinese rule. In 1928 a major revolt took place around the ancient Khanate of Kumul – known to the Chinese as Hami – in the east of the province. In the mid-1930s the Uighurs of the Tarim Basin broke away from China, and established the short-lived "Turkish-Islamic Republic of Eastern Turkistan". This, in turn, was followed by the pro-Soviet "East Turkistan Republic" which controlled north-west Xinjiang until the Chinese Communist seizure of power in 1949.

When the PLA entered Xinjiang in 1950, the province remained very much a Chinese colony in the heart of Central Asia. Statistics from the time show that Han Chinese numbered only 200,000, or between three to four per cent of the population. Turkic-speaking Muslims – chiefly Uighur, Kazakh and Kirghiz – by contrast, comprised an overwhelming 93 per cent. The victorious Chinese communists were unified and immensely powerful, however, whilst the Turkic Muslims – especially the dominant Uighur nationality – were divided, leaderless and weak.

Over the intervening nearly five decades the communist authorities in Beijing have done everything in their power to consolidate their hold on Xinjiang, chiefly by promoting massive Han immigration. Today the ethnic balance in the province has swung sharply in China's favour, with Han settlers making up slightly more than half the population. At the same time every effort has been made to isolate the Uighurs from their fellow Turkic Muslims elsewhere in Central Asia – a task which has now become harder with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The people of Xinjiang have witnessed the emergence of independent Kazakh, Kirghiz, Uzbek and Tajik states along their western borders. Understandably they want no less for "Eastern Turkistan"; in China's great Central Asian territory the natives are increasingly restless.

The separatist goal of an independent Xinjiang won't be won easily, however. To begin with, there are a great many more Han Chinese than there are Uighurs. Most Han don't want to move to Xinjiang – it has always been seen, and feared, as a place of exile. By combining a judicious mixture of carrot and stick, the authoritarian regime in Beijing has moved millions of people westward, and intends to move more. Plans exist, for example, for more than a million Han farmers displaced by the Three Gorges Dam to be resettled in western Xinjiang, securing China's ethnic hold on the Kashgar region. Uighur nationalists are aware of this policy, and strongly oppose it. They know all too well that in Inner Mongolia Han Chinese now outnumber the indigenous Mongols by twelve to one!

Another problem facing the "splittists" is lack of effective external support. When the communists took over in 1949, many Uighur nationalists fled across the Himalayas to India. Subsequently most settled in Turkey and Saudi Arabia, two countries generally sympathetic to their cause, but geographically far removed from Central Asia. At present none of the neighbouring Central Asian states seem willing to provide material support for the Uighur nationalists, though some arms do find their way to the Tarim Basin from sympathetic factions in fractured Afghanistan. Only if the Islamic opposition in war-torn Tajikistan comes to the fore is this situation likely to change.

Which brings us to the last of Beijing's charges – that the Xinjiang "splittists" are Muslim fundamentalists. This is almost certainly false. There is no tradition of fundamentalism in Xinjiang, even in the conservative Tarim Basin. The Uighurs are Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school, just like their non-fundamentalist Uzbek neighbours. Many Xinjiang Kazakhs don't even bother to circumcise, and indulge readily in drinking kumiss , or fermented mare's milk. There are no indications of links with radical Sunni groups like the Muslim Brotherhood – indeed precious few links with the Arab World at all. By the same token Iranian influence is virtually non existent, as the only Shia in Xinjiang are a few thousand "Mountain Tajiks", widely despised by the Sunni majority as impoverished heretics.

In sum, what the Chinese face in Xinjiang is a tide of rising Turkic nationalism, not a religious revolt. In this the situation has more in common with Chechnya than with Iran or Algeria. For the present, it seems likely that Beijing can keep the situation under control, if only through weight of numbers. Like Tibet, though, it's a problem that won't go away any time soon.

SEE MORE XINJIANG IMAGES @ PICTURES FROM HISTORY

Text by Andrew Forbes; Photos by Pictures From History - © CPA Media